How to align the EU fiscal framework with the Green Deal

The EU climate targets require higher public spending. In times of strained national budgets, a reformed EU fiscal architecture must conciliate debt sustainability concerns with green spending needs and foster European solidarity.

The EU’s economic recovery budget “Next Generation EU” is providing fresh funding to member states for investing in green technologies, especially to those most in need. The grants from the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) allow highly indebted governments, in particular from southern EU countries, to support the economic recovery and upscale green investment over the next few years without eroding their already limited fiscal space. Yet, the resources allocated to climate investment through the national recovery plans are far from what is needed to reach the 2030 EU climate targets. EU countries will have to cut more emissions over the next nine years than they have cut during the last thirty years.

The 26.5 billion euros allocated in the plans to the green renovation of private residential buildings is a small fraction of the 380 billion euros of additional public grants we estimate the residential sector needs over the 2021-2030 period. Moreover, the plans will directly support the deployment of only 20 gigawatts of new renewable power capacity, while, according to the Commission, the EU needs approximately 500 gigawatts of additions between 2021 and 2030. Overall, total climate-related expenditures in the 22 national recovery plans approved so far stand at approximately 177 billion euros. This makes on average 0.2% of GDP per year over 2021-2026, yet spending is often frontloaded and provides an important boost to green investment in the short term.

How much green public spending is needed?

Even if governments leveraged as much private capital as possible, effective and just policies will require a significant amount of additional public spending. Governments may have to offer high support to low-income households and small firms, too. Who will pay for the home renovation of the 18% of households in the EU that have incomes below the poverty line? There will also be non-investment-related public expenditures, like unemployment benefits and retraining programmes for workers in declining sectors, as well as compensation to low-income households and small firms if energy costs rise during the transition.

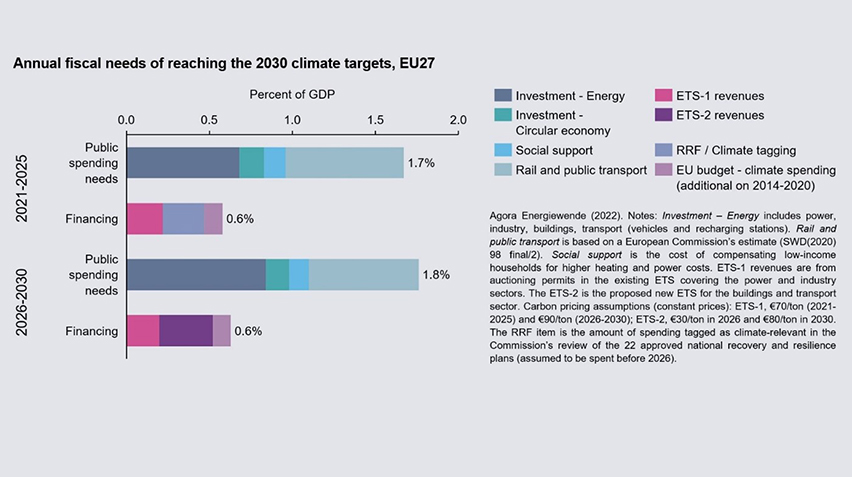

We estimate that green public spending needs for the 2021-2030 period will exceed 1% of GDP per year in the EU, as the chart above shows. This is larger than other estimates that only consider investment-related expenditures or exclude investment in rail and public transport infrastructures (if based on the Commission’s modelling figures), and is in line with an in-depth analysis of German green spending needs. The amount can be reduced if governments rely more on carbon pricing and regulation, but this option faces significant political hurdles. Spending for climate change adaptation and other environmental areas (biodiversity, forest, wastewater, and water management) should be added on top.

Carbon pricing and the phase-out of fossil fuels will structurally change national public budgets

The existing Emissions Trading System (ETS) should generate 30 billion euros per year in auction revenues if prices average 70 euros per tonne of CO2 in 2021-2025 and 90 euros per tonne in 2026-2030 (at constant 2020 prices). This amount, 0.2% of GDP, falls short of covering spending needs. The proposed ETS for buildings and transport could bring additional revenue worth 48 billion euros per year (0.3% of GDP) between 2026 and 2030 if it were to be finally approved by the EU Council and Parliament. After 2030, carbon pricing revenues will decline unless prices keep up with falling emissions, and electrification will start eroding a large share of the revenue that governments earn from motor fuels taxation (up to 3% of GDP in Greece), putting a strain on national budgets.

Current fiscal rules require consolidation

EU member states must adhere to a set of fiscal rules known as the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), which prescribes that budget deficits should not exceed 3% of GDP and debt levels must stay below 60% of GDP in the long term. Under these rules, which have been suspended since 2020 under an emergency clause but will most likely be reinstated in 2023, member states with large deficits will need to make considerable fiscal adjustments starting in 2023.

The EU economy is recovering from the COVID-19 crisis, but the pandemic has brought the average government debt-to-GDP ratio in the EU from 79% in 2019 to 92% in 2021. Countries with already high debt ratios were the countries that saw the largest increase during the crisis. In the euro area, 12 out of 19 countries will exceed the 3% deficit criterion in 2022. According to national projections, nine countries will also exceed the threshold in 2023, which can lead to the opening of an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) under the corrective arm of the SGP.

Furthermore, all member states will exceed their Medium-Term Budgetary Objectives (MTO) – an indicator under the preventive arm of the SGP that represents the cyclically adjusted government deficit – and most will exceed it by a large margin. Countries that do not meet their MTO must pursue an appropriate adjustment path towards it that depends on their respective debt level, debt sustainability, and output gap. If the output gap is higher than -1.5% of GDP, which according to current projections (and calculation methods) will be the case for most member states in 2023 and beyond, the required annual deficit reduction is at least 0.5% of GDP.

Given a long-lasting increase in public green spending needs of more than 1% of GDP, this is a cause for concern. As the impact on national budgets will be permanent, the SGP’s investment clause will not help. Moreover, evidence from previous fiscal consolidations shows that public investment tends to be sacrificed during consolidation periods because of political economy constraints. This in turn can harm economic growth and debt sustainability itself.

Implications for reform

Additional green public spending needs require deficit spending beyond what current fiscal rules allow. And there are good reasons to fund green spending with deficits: public spending needs are massive and can hardly be funded from current revenues alone. Furthermore, future-oriented spending on green infrastructure and technologies will last for decades and benefit future generations. Therefore, from an intergenerational perspective, deficit funding of green spending is reasonable – even more so given low interest rates. Yet, debt sustainability concerns as well as ambiguous growth implications of green spending cannot be ignored. Recent surges in government yield spreads of some highly indebted countries – including Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal – following rising market expectations of possible monetary tightening reflect these concerns.

It follows that any reform should satisfy at least two conditions: First, it should ensure that green public spending needs are met. This is non-negotiable given the severe consequences of runaway climate change. Second, any reform should not hinder economic convergence, and must promote growth-friendly debt reduction.

A “green golden rule” that would exempt certain green investments from fiscal indicators is regarded by some as a reform option that satisfies both conditions. Although a popular proposal, it is unclear how exempting green spending in highly indebted countries would address investors’ concerns over debt sustainability or affect the debt sustainability of these countries. Other reform proposals, e.g. an expenditure rule, could promote a gradual reduction of debt levels through better countercyclical properties, but would not guarantee sufficient green spending. Such reforms would have to be complemented with a permanent fiscal facility that supports predefined green spendings in the most fiscally fragile countries.

Like the RRF, a permanent fiscal facility would have redistributive elements via joint EU borrowing and, possibly, distribution of grants, which would support countries with fragile public finances. An advantage would also be that, as with the RRF, receipts of funds, loans or grants, could be conditioned on achieving agreed-upon milestones and implementing growth-friendly reforms, which would also help bring down public debt levels in high-debt countries.

Whichever combination of reforms is agreed upon in the end, policymakers should ensure that the fiscal framework supports the successful implementation of the EU Green Deal.

This blog post is a product of an ongoing project on this topic, and we will publish a paper with detailed results at the end of March 2022.